Organ donations save lives, but not enough people donate. Is an opt-out system the solution that will work in England right now?

England introduced deemed consent for organ donation in May 2020. This means that all adults in England are now considered to have agreed to be an organ donor when they die unless they have actively recorded a decision not to donate or are in an excluded group. While family permission for donation is still sought, the goal of this change is to “boost organ donation rates” according to England’s health secretary, Matt Hancock. However, what does evidence from other countries that have made this change tell us about the likely success of this move?

“Too many people lose their lives waiting for an organ, and I’ve been determined to do what I can to boost organ donation rates” – Matt Hancock, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care

In the UK, Wales was the first to move to a soft opt-out system at the end of 2015. Dr Dale Gardiner led a team in comparing consent rates for decreased donation in Wales and England between 2016 and 2018 to examine the impact of the different systems. The results show some promise for the move to a soft opt-out system. Specifically, the proportion of families consenting to organ donation following brain death in Wales increased, with the difference in the proportion of families consenting in Wales and England reaching statistical significance after 33 months of the soft opt-out system being in place. However, in contrast, no change was observed in the proportion of families in Wales consenting to organ donation after circulatory death following the introduction of the soft opt-out system.

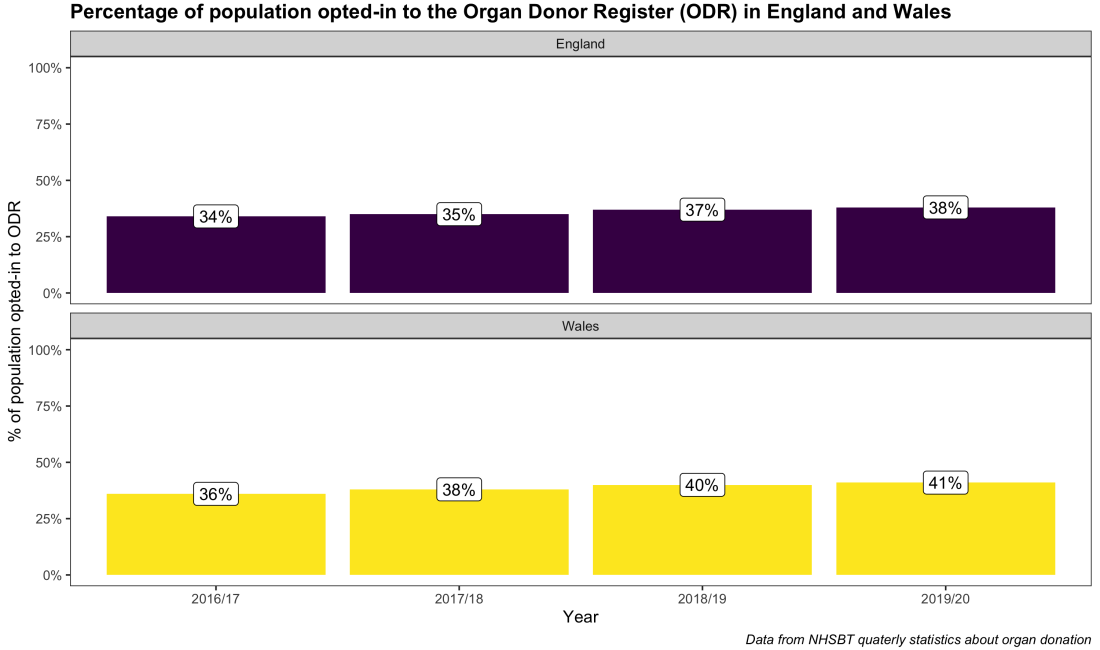

NHS blood and transplant publishes quarterly statistics about organ donation which allow us to continue looking at the difference between England and Wales beyond 2018. While we cannot see the proportion of people whose organs were consented for donation upon their death, we can see trends in the number of people actively registering their consent to donate (opting-in) on the Organ Donor Register. This shows that since 2016 both England and Wales have had comparable upward trends in the percentage of their population opting into the Organ Donor Register. This trend toward active consent in both opt-in and opt-out systems raises the question of ‘if those who want to donate are registering, then what will a change to the organ donation system in England actually achieve?’

Of course, the obvious answer to this is that the default in opt-out systems favours donation. Presuming that not registering (to donate or not) reflects only inertia, then soft opt-out systems should theoretically result in more organs being donated. While Gardiner and colleague’s analysis suggests some early positive results in Wales, the focus has been on consent rates. However, moving beyond consent rates not all countries who have moved to a soft opt-out system have seen an increase in organ donation rates. Countries like Belgium experienced successful increases in donation rates but other countries such as Singapore, Chile and Sweden have not experienced increases in donation rates after the introduction of soft opt-out systems.

Arshad and colleagues compared organ and transplantation rates across 35 countries, of which half followed an opt-out system and the remainder had opt-in systems. There were no significant differences in the rates of deceased donation between the two systems. The authors concluded that moving to opt-out does not provide a quick and easy fix to low rates of organ donation. This means that the consent system adopted may not be the solution to the problem of organ donation shortages we see. Instead, Arshad and colleagues recommend improving information and education of the public to improve organ donation rates.

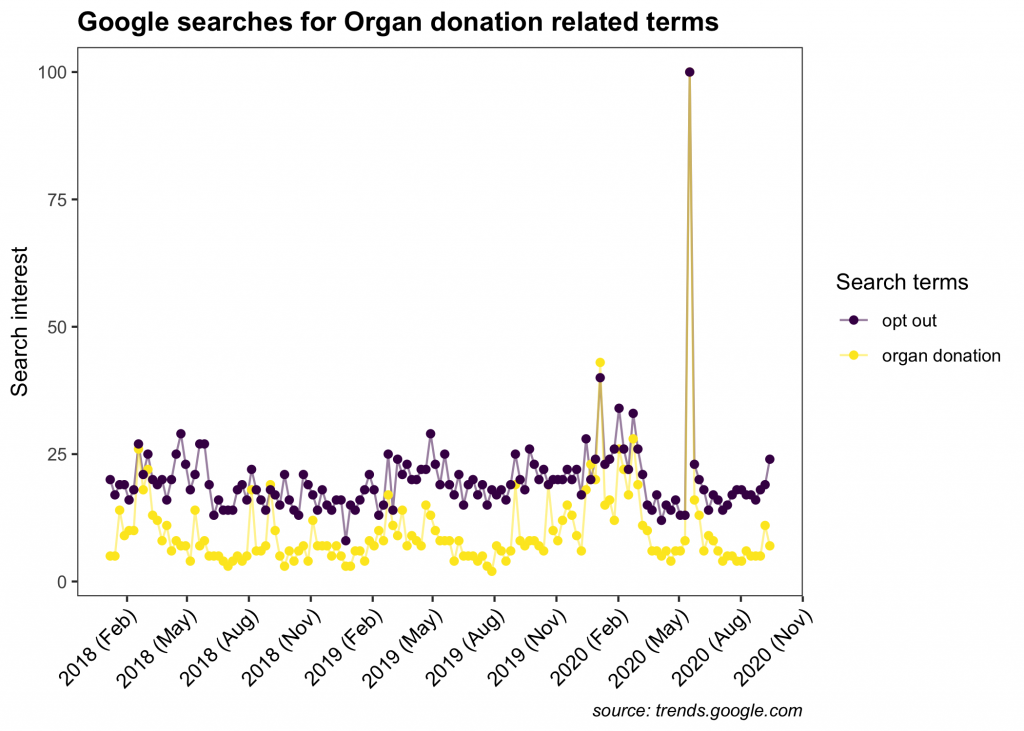

So, what of the situation in England? Without a doubt, COVID-19 has added a layer of complexity for organ donation, with concerns that information and education of the public about the new opt-out system have been lost in the noise of the pandemic. In a recently published paper, Parson and Moorlock argued that “COVID-19 dominating headlines will prevent widespread awareness of the change, thereby undermining the autonomy of those who do not wish to be donors”. In the United Kingdom, COVID-19 cases are again rising and attention is once again firmly back on the virus, and the locality of cases. In the UK, Google searches for coronavirus and symptoms increased by around 36% on the day immediately after the announcement of local cases, with interest levels decreasing to baseline after two-weeks. Has there been a similar buzz around organ donation given the significant change from opt-in to soft opt-out that came into effect on the 20th April 2020? The short answer is ‘no’. When we examined Google search data in England for terms related to organ donation, we see peaks of interest when the opt-out system received Royal Assent (15/03/2019) and came into effect (20/04/2020), but with overall search activity relatively low. This suggests that, consistent with Parson and Moorlock’s concern, with COVID-19 clearly front and centre of people’s health concerns, the information and education needed to make soft opt-out systems of organ donation successful has not yet been received.