Opt-out Organ Donation:

The simple solution to the worldwide donor shortage?

By Dr. Jordan Miller

By Dr. Jordan Miller

Organ Donation is lifesaving. However, across the world, there is a serious gap between the number of people waiting for an organ transplant and the number of organ donors. Although the number of donors has increased globally by 6% since 2017, unfortunately, current rates of transplantation satisfy less than 10% of global need. This shortage is compounded by the fact that only a very small number of people (just over 1% of deaths in the UK and 2% in Australia) die in situations that make it possible for them to be eligible organ donors. As such, exploring strategies to increase the number of organ donors is of critical importance.

Strategies to Increase the Number of Donors

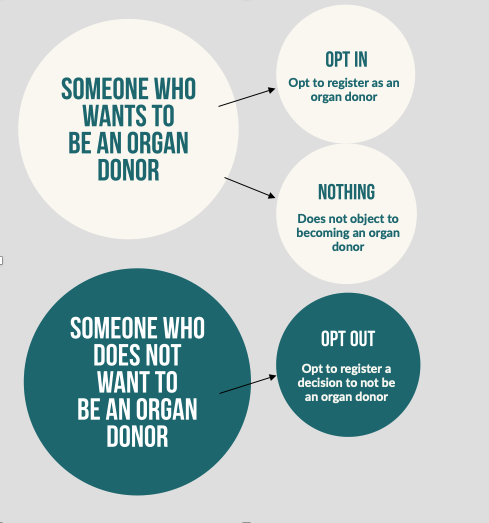

Current efforts to overcome the donor shortage, have focused on altering the way consent for organ donation is recorded. In most nations across the world, consent systems broadly follow two approaches; opt-in or opt-out systems. Under an ‘opt-in’ system, a person can indicate their donor decision by providing explicit consent for organ donation. This usually involves signing-up (opting-in) to a nation’s organ donor register, carrying a donor card or by verbally expressing a donation decision to family members. The downside to this system is that although support for organ donation is usually very high, this often does not translate into actual donor registrations. Using the UK as an example, while around 80-90% of the public have positive attitudes towards organ donation and say they want to donate their organs, just 40% have actually registered as donors.

Under an opt-out system (also referred to as a deemed or presumed consent system), there is no requirement for a person to actively register as an organ donor. Instead, if a person has not made a decision about organ donation, they are automatically deemed, by law, to have consented to the donation of their organs. If a person does not want to be a donor they can record this decision by actively opting out of the register. A key reason for changing the system is that altering the default position to consent, should bridge the gap between the public’s favourable organ donor intentions and their inaction, ultimately increasing the number of potential donors.

Because the concept of opt-out consent is a relatively recent change to the traditional opt-in or express consent system, almost no research has focused on understanding attitudes towards this new law or explored why people may opt-out of organ donation. We need to understand the barriers under this new system, particularly in the UK, where last year, more people opted-out of organ donation and registered not to donate their organs than those who registered as donors.

To address this, as part of my PhD research, we (Jordan Miller, Ronan O’Carroll, Sinéad Currie and Lesley McGregor) conducted qualitative interviews with 15 participants in the UK who plan to opt-out of organ donation. In this study, we explored participants attitudes towards organ donation, their views on different consent systems and importantly, their reasons for opting out.

The Role of Emotional Barriers

Throughout, participants described a number of negative emotional beliefs to play a role in their donor decision. A number of studies have shown that feelings and emotional beliefs are important when making organ donor decisions. In this study, participants emphasised the role of two emotional barriers, medical mistrust and bodily integrity concerns, as key factors in their planned decision to opt-out.

Medical Mistrust was represented by a deep-rooted unease that, in the event of life-threatening injury, doctors inherently motivated to utilise valuable organs, may not act in a patient’s best interests. Throughout, this manifested as the belief that doctors may provide a lesser life-saving treatment to patients who are identified as potential donors. In addition, participants also expressed fears that doctors may hasten or prematurely declare their death and that consequently they would be alive while their organs were being removed.

I guess it’s the “what ifs”, it’s the y’know what if you aren’t really dead and all this sort of nonsense

and the sensible side of me is telling me not to be stupid but the not so sensible

side y’know is still questioning it…

Bodily Integrity concerns the belief that the human body should remain whole and undamaged after death. In this study, participants believed that organ donation would violate the physical integrity of their body, leaving it in a disfigured state after death. Throughout, participants often used word choice such as “mutilated” and “tampered”, to emphasise their concerns.

However, it also became clear that unique factors, including notions of coercion, heightened government control and loss of freedom of choice, which are arguably specific to the nature of an opt-out policy may also play a role.

Consent Versus Coerion

Not surprisingly, participants strongly favoured the traditional opt-in system, where consent is recorded when a person joins the organ donor register. It was thought that actively taking the time to register as an organ donor, clearly demonstrates their consent to have been informed and the decision, a voluntary choice.

As a nurse before I do anything I ask for consent so I don’t just like go and take somebody’s blood and

then go “is that okay that I’ve just taken your blood?” so in my opinion, you need to ask for consent

and that’s what it [an opt-in system] does, it asks for consent.

However, the opt-out system was perceived as forceful and intrusive. Throughout the interviews, participants expressed the view that this new system signified unwarranted government interference into a highly personal decision. For some, this was considered to give the government illegitimate ownership over their body after death. As consent for organ donation will be presumed automatically for those who have not registered a decision, many believed this would “remove their choice and their voice” and threaten their “free will to make their own decisions”. Taken together, it seems that the decision to opt-out was driven by a desire to protect one’s freedom of choice. In line with this, these concerns may be best understood to represent reactance.

Psychological Reactance

Have you ever been told not to do something, and suddenly developed almost an unquenchable urge to do just that?…well, you have likely experienced reactance.

Reactance occurs when a person feels their behavioural freedoms are being restricted. We all have a sense of behavioural freedom, which includes choices or actions we think we have a right to enact without restriction or coercion from others. In this example, the decision not to be an organ donor can be classed as a free behaviour. This free behaviour subsequently becomes much more important when a person believes it to be under threat.

Reactance is found to play an important role in guiding one’s responses to health communication campaigns. For example, if a person reads something that is considered to limit their freedom, they may experience a mix of anger and hostility towards the source of the threat. This subsequently motivates a person to take action to restore their autonomy. This often takes the form of a boomerang effect, whereby a person who experiences reactance may engage in oppositional behaviour to reinstate their sense of freedom (for example, drinking alcohol after exposure to alcohol reduction campaigns).

Overall, what is most interesting about these factors, is that they are distinct to traditional organ donation barriers. Arguably, these factors aren’t specifically related to organ donation in the same way as medical mistrust for example, but are linked to the nature of this sensitive new default system.

Going forward, developing a clearer understanding of the potentially novel factors influencing organ donation decisions under opt-out consent is a crucial area that future research should target.

About the author

Jordan is a Research Fellow at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. She completed her PhD at the University of Stirling, Scotland in 2021. Her PhD research applied a mixed-methods approach to examine the role that affective attitudes play in donor-relevant decisions, for example, disgust at the thought of organ donation, or concerns of medical mistrust. Her research included both an examination of individual determinants of donor behaviour and of the factors that influence family decision-making for posthumous organ donation. Jordan’s PhD research had a particular focus on the impact of modern policy changes in organ donation legislation (opt-out versus opt-in consent) and identifying potentially novel factors that might influence donor relevant decisions under opt-out legislation, such as psychological reactance and government trust.