Do incentives encourage blood donation?

By Caroline Graf (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam)

Blood donors often receive small gifts like mugs and flowers to motivate them to donate. In some countries blood donors even receive items of quite high value, including financial incentives (for example cash or tax benefits) or non-financial incentives (for example allowing donors to take the day off or even offering them a chance to win a trip to the Super Bowl). But are (potential) donors actually attracted by such incentives? Or are donors instead discouraged, perhaps because they want to be perceived as giving blood to help others and not to get something in return?

Let’s start at the beginning. Why would one want to use incentives to encourage a specific behavior in the first place?! Well, incentives play a key role in economic theory. Let’s take a quick detour to classical economics. According to the basic supply and demand model (as sketched to the right), there is more supply of a good or service when the price of the good or service increases. Therefore, this model predicts an increased supply of blood donors when blood donation is incentivized (because the incentive represents a price increase). This basic principle is widely accepted among economists: Incentives matter!

However, blood donation is not a typical “market transaction”, and actually incentives for donating blood are heavily debated. Some think that it is both immoral (due to negative societal effects and safety concerns, as illustrated for example in the documentary “Blood” about remunerated donors from Russia) and ineffective to lure donors with incentives — as incentives are argued to decrease people’s motivation to donate blood. Others deem it irresponsible not to compensate blood donors, because they see incentives as a means to both encourage donation and appreciate donors for their good deeds.

You may ask: Isn’t there empirical evidence which can offer a clear and unequivocal answer to whether incentives should be offered to blood donors or not? Unfortunately, there is no such easy answer. There is evidence both in favor and against using incentives. A recent review of studies found that the effectiveness of incentives in encouraging blood donation varies heavily across studies. Empirical investigations from different countries, using different types of incentives, showed sometimes positive, at other times negative, and in yet other cases no effect of incentives. So, we (and also policy-makers) are still left in the dark regarding whether incentives can be used for encouraging blood donation and other types of prosocial activities.

In our current project, we (Caroline Graf, Eva-Maria Merz, Pamala Wiepking and Bianca Suanet from VU Amsterdam and Sanquin Research) set out to shed some light on these inconsistent effects of incentives on blood donation.

So far, theory suggests that the mechanism by which incentives backfire is a cost to the donor’s reputation, because receiving an incentive signals that the donor may just be interested in the incentive instead of donating to help patients in need. But do incentives always lead to such a reputational cost?

We were inspired by insights from evolutionary biology and psychology to question this assumption that there is always a reputational cost. According to research in these disciplines, the consequences to a person’s reputation depend on social norms, which are the informal rules that govern what is viewed as an acceptable or appropriate behavior. We can apply this concept of social norms to incentives for blood donation. Social norms regarding incentives reflect how acceptable members of a given society view receiving a specific incentive for donating blood.

And this may vary across (cultural) groups. In some societies it may be appropriate to receive time off work for donating blood, but not financial incentives; whereas in others financial incentives may be considered acceptable, because they pay tribute to the critical role donors play in enabling life-saving medical procedures. Norms thus have an apparently arbitrary character, and yet any one individual in a society perceives these informal rules as extremely natural. Think for example about how it is appropriate to gift cash when attending a wedding, but not when attending a Thanksgiving dinner — very different gifting norms apply to these seemingly similar social activities! (Plus, not surprisingly, gifting norms vary widely across the globe!)

To test whether social norms play a role for the relationship between incentives and blood donation, we compared blood donors across Europe using large-scale survey data. We were able to take this comparative approach, because European countries have adopted various incentive policies for blood donors.

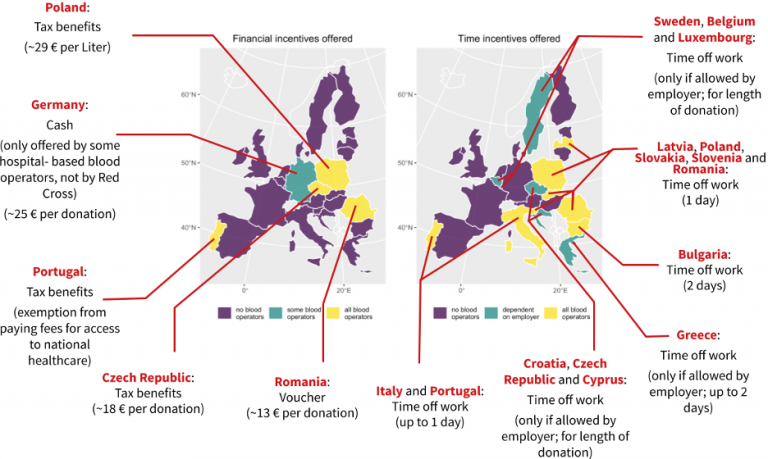

As a first step, we interviewed blood operators across Europe about what high-value financial and non-financial incentives are offered to donors in their country. Here is what we found:

The map on the left shows the locations in Europe where high-value (>10 €) financial incentives (e.g., tax breaks or cash) are offered. Only a few European countries provide financial incentives to blood donors. On the other hand, time incentives (as shown on the map on the right) are more commonly used to incentivize blood donation. 15 out of 28 European countries offer some form of time incentive. However, some countries offer time incentives to all donors; whereas in other countries the donor’s employer must give permission (this is typically the case for government employees).

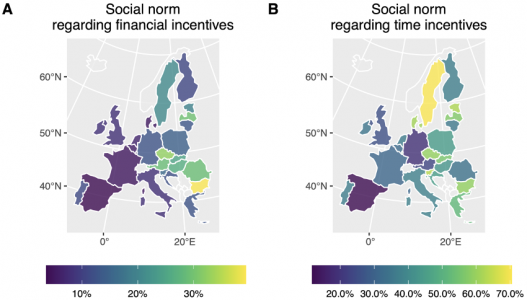

Based on data from the multi-national Eurobarometer survey, we were also able to examine social norms regarding incentives. More specifically, we looked at views on how acceptable receiving a certain incentive for blood donation is in a given European country:

As you can see in these two maps, social norms varied across countries and also across financial and time incentives. Overall, time incentives were viewed more positively than financial incentives. But even for financial incentives, acceptability ranged from 90% of the population finding financial incentives unacceptable (for example in France) to 40% of the population finding financial incentives acceptable (for example in Bulgaria).

But how do these incentives and norms relate to individual-level propensity to donate blood? Our analyses of more than 25 000 people living in 28 European countries revealed that different incentives have different effects in different countries: Although financial incentives overall had a negative effect on an individual’s likelihood to donate blood, this negative relationship was less strong in countries with more positive norms regarding financial incentives. That is, the more favorably financial incentives were viewed in a given country, the higher an individual’s donation likelihood. We observed a similar pattern of behavior for time incentives, but in contrast to financial incentives, time incentives themselves were neither negatively nor positively associated with propensity to donate. We found that time incentives were positively associated with blood donation behavior if social norms regarding time incentives were relatively positive. However, if social norms were instead relatively negative, then time incentives were actually associated with lower levels of blood donation.

Our findings show that social norms can indeed explain patterns of real-world prosocial behavior across countries, including the effects of different types of incentives on prosocial behavior. These findings highlight that no man is an island. People’s cultural environment, which includes norms that have culturally evolved over long periods of time, subtly shapes individuals’ attitudes, perceptions, and ultimately, behavior. In our case, taking into account cultural context unveiled exciting new insights into how incentives can be used to encourage blood donation.

In sum, the answer to the question in the title is: It depends! Incentives can encourage blood donation, if the incentive is found to be acceptable in a given society.

* * *

If you are curious to learn more about this research project, you can access the preprint here. For questions and comments you can also contact Caroline (c.graf@vu.nl) or Eva-Maria (e.m.merz@vu.nl).

About the author

Caroline Graf is a PhD candidate at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the DONORS project led by Eva-Maria Merz. Within this project, she examines the role of cross-cultural differences in shaping people’s motivations to do good, currently with a focus on blood donation behavior.

She has a background in Cognitive Science and is interested in interdisciplinary approaches to understanding behavior.